By Gene Tinnie

“Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world; indeed, it’s the only thing that ever has.”–Anthropologist Margaret Mead (1901-1978)

Some of the best proof of these words came to life seventy-seven years ago in Miami-Dade County on May 9, 1945, and on that occasion, “courageous” would be an apt addition to the description of the five men and two women reported to have “waded in the water” on that spring morning where present-day Haulover Beach was under construction to be a future County Park.

A few people taking a dip in the ocean, even at this unusual location, in a county known worldwide for its miles of scenic beaches would usually not be anything out of the ordinary, but this was not an ordinary time or place. The time was the era of Jim Crow segregation, and the place, for all of its worldwide fame as sun and fun destination, was very much part of that segregated American South, where those who dared to cross the enforced “racial” dividing lines did so at their peril, even more so if the violators were classified as “Negroes” or “Colored,” deemed by law and custom to be encroaching on undeserved privileges which were reserved for those who claimed to be “White,” including exclusive use of all of the region’s beaches.

But 1945 was a time of profound change: World War II, which had cost the world tens of millions of lives, in addition to years of suffering and deprivation, was finally nearing its end, and with it came the rising demands of the “Double ‘V’ Campaign” waged by African Americans during the war, for Victory against fascism and dictatorship abroad and Victory against racism and injustice at home.

Black military personnel and their communities alike were resolved that they would come home to better conditions in the nation they fought for than what they had endured before and during the war, including witnessing German and Italian enemy prisoners of war being treated as “White,” with more freedom, respect, and privileges than Colored soldiers and sailors, even in uniform, and while Miami was no exception, it would be exceptional.

Fort Lauderdale Wade-Ins

Via Florida State Archives at www.FloridaMemory.com

A Unique Situation

If Miami’s beautiful beaches were among the region’s most valued assets, and a vital key to reviving the local economy as the nation emerged from war, then that revival must include, unlike the prewar years, at least one oceanfront bathing beach where Colored veterans and their families and communities could go freely.

Significantly, this was not a demand for integration of the beaches, but for a separate-and-equal park, as stipulated by segregation law, free from racist social interactions, and in Miami this had special meaning because of the city’s unique historical roots, on both sides of the “racial” divide.

On the one hand, it will be recalled that Miami is located near the southern end of a peninsula that had long been “Freedom Land” under Spanish rule for Native and African Americans liberating themselves from settler invasion and slavery, who established Maroon settlements and Underground Railroad escape routed to freedom before it became part of the U.S., and even afterwards Florida never had widespread large-scale plantation slavery as in the states to the north of it.

Moreover, the primary early Black settlers of Miami specifically were Bahamian immigrants, many of whom were literate and educated, and would comprise as much as half of the signers of the charter that established the City in 1896 (the very same year that the U.S. Supreme Court sanctioned segregation laws in the South), and they would be joined by African American railroad builders and others from elsewhere who would make Miami their home, and who, notably, would flip segregation restrictions from being a tool of oppression to a catalyst for Black independence and prosperity.

On the other hand, Miami, Florida was very much part of the south and of the White supremacist triumphalism that emerged after 1896, with the erection of Confederate memorials and a resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan along with incidents of routine racist terrorism, including murders and at least three lynchings, all of which made such a concept as Negro access to oceanfront beaches all but unthinkable before the war years.

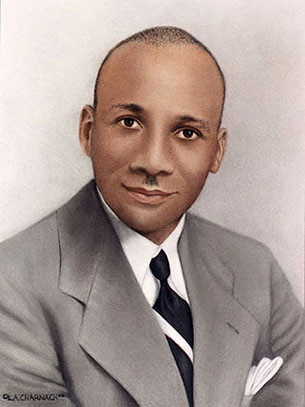

Then came 1945, when the Black community led by activists like Attorney Lawson E. Thomas, Dr. Ira P. Davis, Father John Culmer, and Longshoremen leader Judge Henderson, resolved that the time had come to act on the “Double V Campaign,” and that in Miami there would be no more appropriate way than to demand a Colored bathing beach.

With prescient insight and vision, they mobilized the community to engage in Civil Disobedience protest with a wade-in protest at the site of a future White-only beach, fully a decade before such tactics would become a staple of the nonviolent Civil Rights movement.

‘Many Are Called, but Few Are Chosen’

The strategy of Civil Disobedience meant a willful, public breaking of unjust laws and a willingness to be arrested, so, accordingly the Sheriff would be notified beforehand, with Lawson Thomas on hand with copious cash to pay bail and avoid jail time for those who might be arrested, which would force the case to go before the courts and potentially become a great embarrassment to the County and its efforts to attract tourism.

There was enthusiastic support in the community, which increased as May 9, the date chosen for the protest approached, with many promising to join.

It is fair to say, however, that the night before that morning gave many of the would-be participants time to pause and reflect on the possible consequences: An arrest record – which might have become a badge of honor during the Civil Rights era years later – in 1945 could ruin one’s livelihood permanently, (as the question would appear on every job application) and taint one’s reputation in society.

Even more daunting was the very real prospect that, in the unwritten codes of “Southern Justice,” the protestors might not be met by the sheriff doing his legal duty, but rather than Klan thugs who might have been assured that they would face no punishment for whatever actions they took against “troublemakers.”

These considerations are what made the courage of the undaunted few who kept their promise so remarkable, and this was certainly a determining factor in the sheriff’s determination not to make any arrests, making a call instead to County Commissioner Crandon for advice, who agreed to meet discreetly with Attorney Thomas and “work something out.”

That “something” would be a victory for the many, with the official opening of “Virginia Beach,” on August 1, 1945, on a half-mile of scenic shoreline along Bear Cut, which separates Virginia Key from Key Biscayne, at a location that African Americans had been using for recreation unofficially for decades, which had figured more than a century earlier in the Seminoles’ quest for freedom.

The new beach park would soon be improved with amenities that were typically unheard of at Colored parks in the South, including a Bath House, Concession Stand, cabanas, rental cottages, and even amusement rides, becoming a much beloved hub of Black social, cultural, and spiritual life that attracted visitors from a wide radius of South Florida in addition to tourists and visiting celebrities, and would remain highly popular even after another protest in 1959 ended segregated beaches and parks in Miami, again well ahead of the rest of the South.

It can be said that in 1945 a few thoughtful, committed, and courageous people changed Miami and the world, and their legacy continues in the present effort to create an innovative 82.5-acre indoor/outdoor historical, environmental, and recreational museum experience at this landmark site.

-30-

Gene Tinnie is a Miami-based artist, writer, and retired educator and immediate past chair of the City of Miami Virginia Key Beach Park Trust.