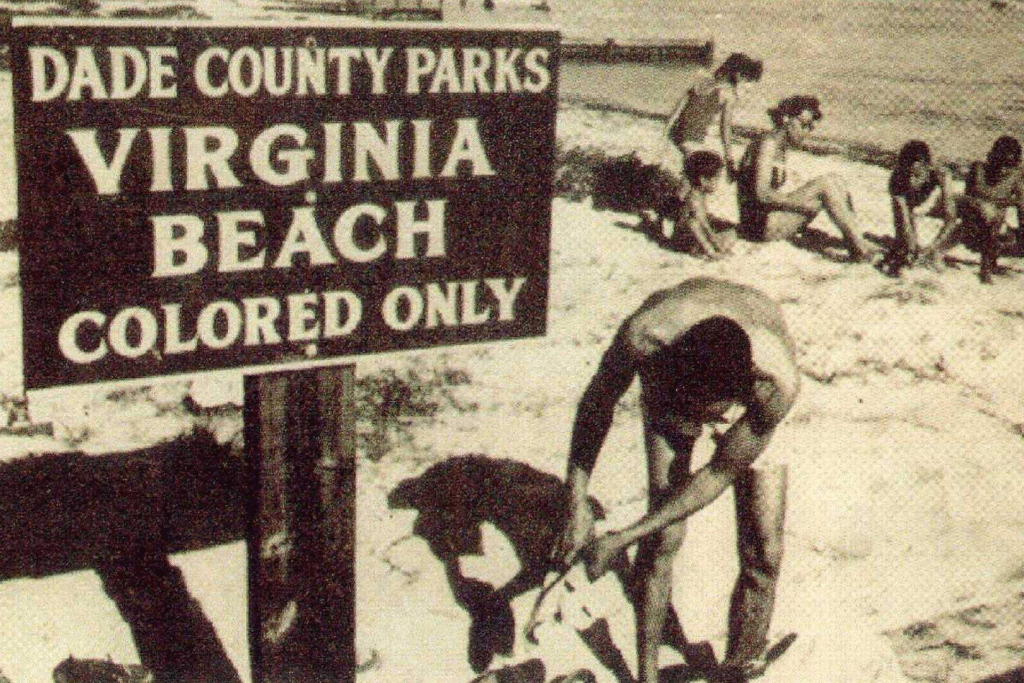

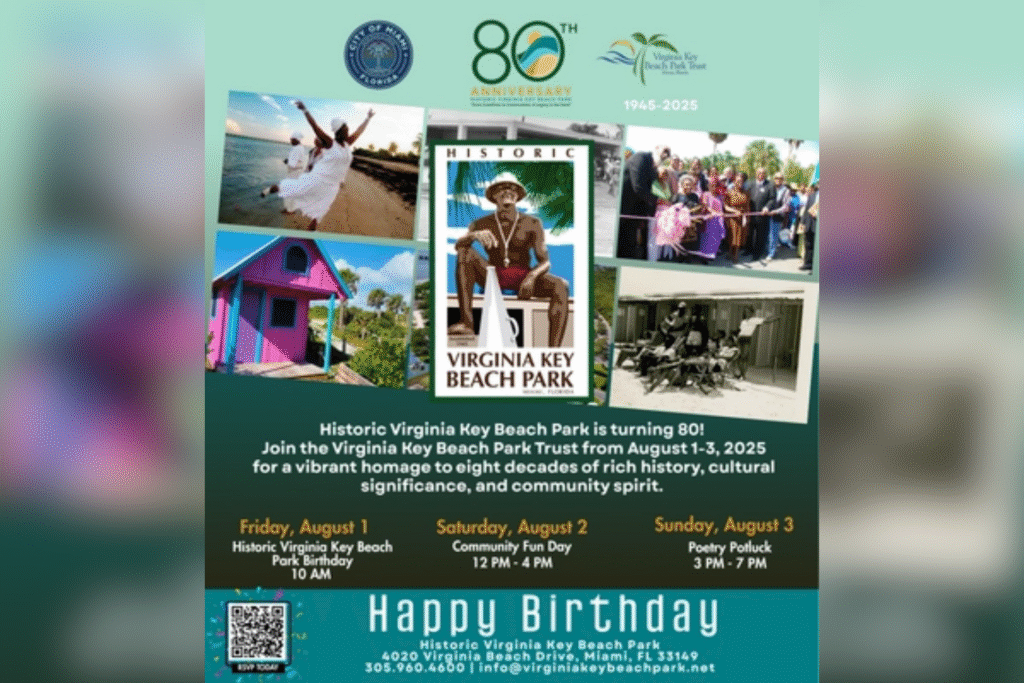

Eighty years. That’s how old Virginia Key Beach, formerly known as the “Colored Beach,” is. When the beach opened on Aug. 1, 1945, I was 7.

Too young to know about the brave men who staged a “wade-in” at the then whites-only Haulover Beach, protesting how Blacks weren’t allowed to go to beaches in South Florida. Thee months after the wade-in, the county opened the tiny sliver of beachfront property just north of the then all-white Crandon Park, to Coloreds (as we were referred to at the time). I didn’t know about segregation and what it meant back then.

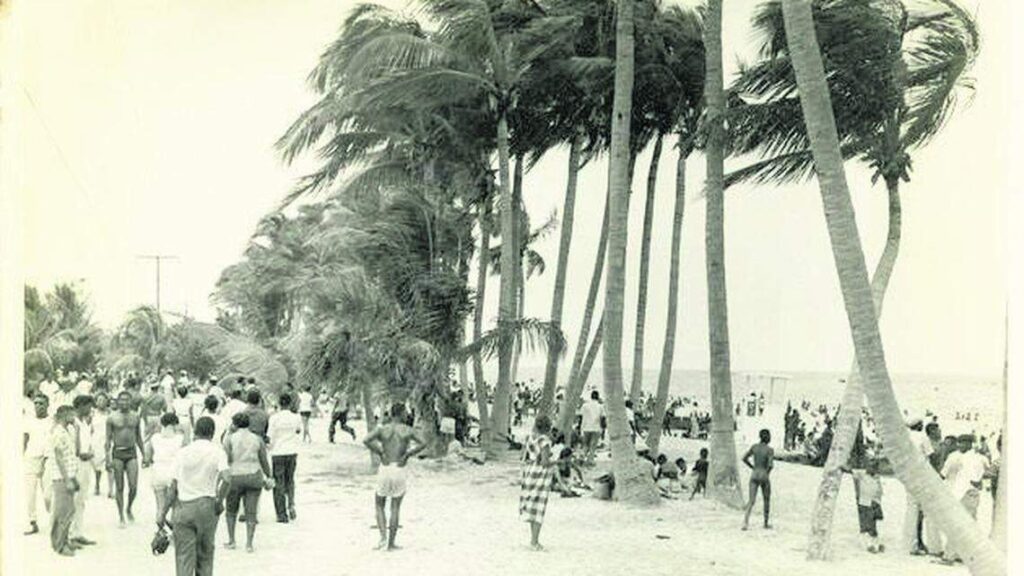

But I still remember the summer days when my mom and her friends gathered us children, packed a lunch – usually fried chicken – and gave us each a rolled towel. Off we went to the Miami River dock where we boarded a boat that took us across the bay to our very own beach. (At the time, you could only get to Virginia Key Beach by boat as the causeway to Key Biscayne was not completed until 1947.) The 25-cents-a-head, round-trip ride across the bay (50 cents for adults) was fun for us children.

We loved to feel the cool water splashing on us as the boat made its way through the waves. Those were fun times for me and my brother. Not so much for our mom, who nervously held on to my brother’s shirttails as he leaned too far over the side of the boat. Once the boat docked near to where the Rickenbacker Causeway is today, we’d run over the hot white sand to a perfect spot near the water.

Mom would spread the blanket over the sand and place our belongings along its edges so the wind wouldn’t blow it up. We splashed and played in the shallow waters along the edge of the beach, while the older kids and adults swam in the deep blue waters.

Then, all too soon, it was time to shake the sand from the blanket, wrap our towels around our wet bathing suits and head to the point where we would be picked up for the return trip to the mainland.

Once there, some of us, like my family, took public transportation back to our neighborhood. Some families had cars, and they would pile in as many people as possible for the ride back home. I guess it’s safe to say that getting to Virginia Key Beach and back was a lot safer for many of us after the causeway opened.

Growing up, Virginia Key Beach was where we held celebrations – birthdays were celebrated there, graduation parties and family reunions were held there. We danced barefoot on a smooth concrete circle to music blasting from juke boxes that were nailed to the coconut trees.

I can still here the tune, “My Little Red Top,” playing as teenagers in wet bathing suits swayed to the rhythm of the tune. Virginia Key Beach was our oasis – a place we could go that would take us away from some of the pain of the Jim Crow era. In 1979, the county transferred the beach to the city of Miami, which closed the park in 1982, citing high mantenance costs. But many of us saw the handwriting on the wall.

The beach was prime property and where there used to be families enjoying the sun, sand and surf, some developers only saw dollar signs. The park was closed for 26 years, not reopening until 2008.

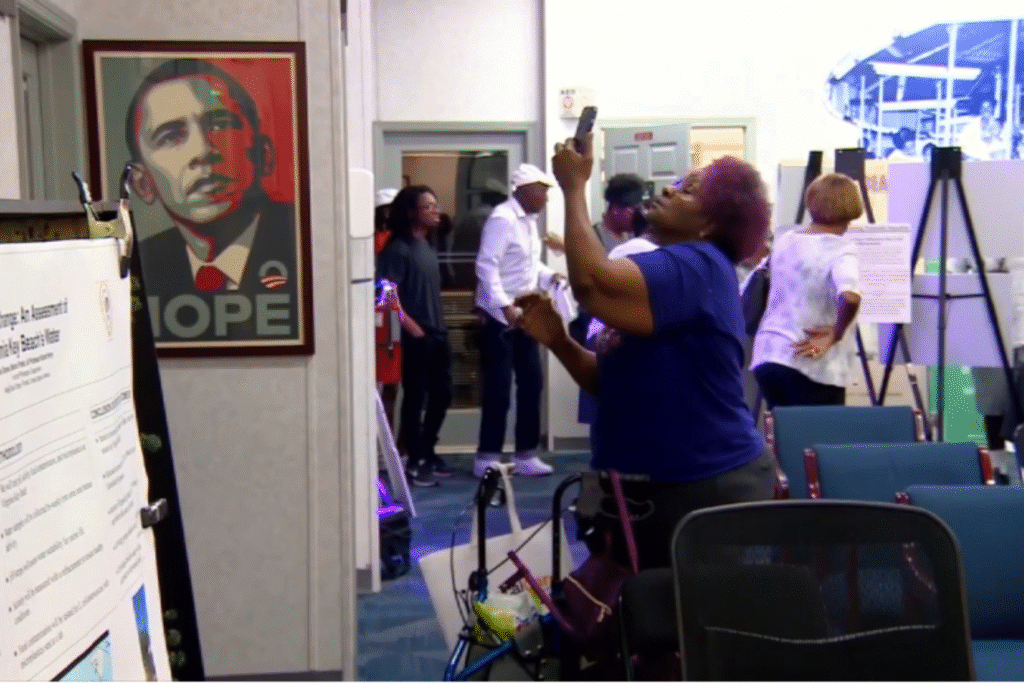

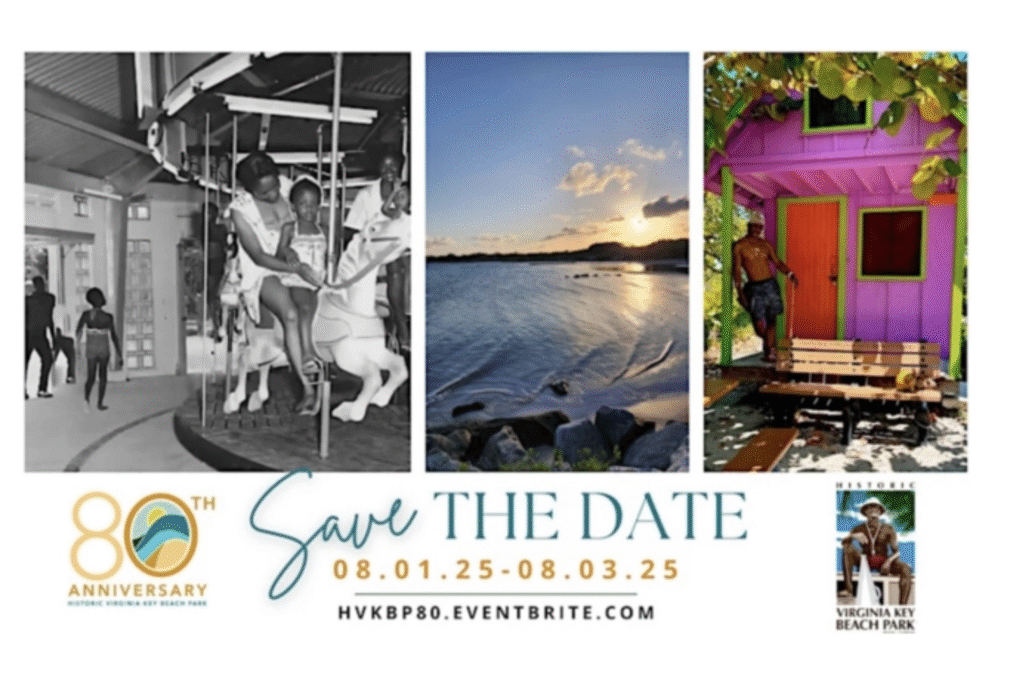

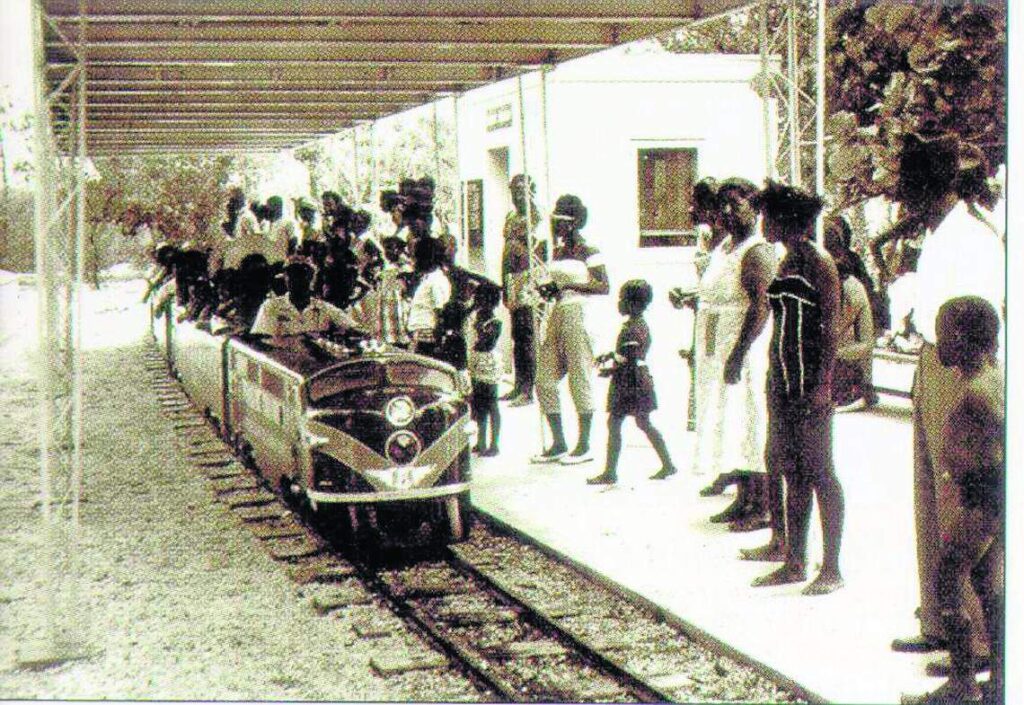

For 26 years, Blacks had no access to the beach/park that held so many wonderful memories for them. It was about that time when a group of citizens, led by the late M. Athalie Range, organized the Virginia Key Beach Park Civil Rights Task Force. In 1999, Miami city commissioners established the Virginia Key Beach Park Trust to oversee the beach’s development. It took thousands of volunteer hours and millions of dollars to restore the neglected beach. The carousel and mini train still need to be restored.

When the park reopened in 2008, it never really got back to the way it was in the old days. While families and others frequented the park, celebrating family reunions and other holidays, there always seemed to be some kind of struggle going on.

Many Blacks were suspicious when in October 2022, the Miami City Commission voted to oust the Trust board, made up of one white and five Black volunteer members. The new board now has seven members — the five Miami city commissioners and two Black lawyers. Of the seven members, only three are Black: Miami Commissioner Christine King, the Trust board chair, and the two lawyers she appointed, Bonita Jones-Peabody and Vincent T. Brown.

In a statement to The Herald in a recent story by Raisa Habersham, King said the beach is “a powerful reminder of the generations whose advocacy turned adversity into legacy” and is a “testament to our community ‘s strength, pride and rightful place in the story of Miami.” While I agree with her, I know that to some, Virginia Key Beach has always and will always have a place in the story of Miami.

People like N. Patrick Range II, who is fighting to restore the beach even though he was kicked off the board. And people like Gene Tinnie, who makes it a point to celebrate the memory of our ancestors, many of whom never made it to shore from the slave ships that brought them from Africa. The celebrations take place during the dawn of a given day. Participants say prayers and bring fresh flowers and fruits that are then placed on a raft of palm leaves taken out to sea in a sacred ceremony. Not only does the ceremony honor our African ancestors, it honors Virginia Key Beach and all that it has meant to Blacks over the years.

Today, the executive director of the Virginia Key Beach Park Trust is Athalie Edwards, who was named for the late M. Athalie Range, the first Black person to serve on the Miami City Commission.

Read more at: https://www.miamiherald.com/news/local/community/miami-dade/community-voices/article311610179.html#storylink=cpy

Entradas destacadas

Categorías